Three-Legged Elephant

by Seán Arena

"Why haven't you travelled more?" asked Jocelyn.

She looked at me from the other side of the cab with a smile that said I know I'm better than you, but I won't say it to your face.

The cab driver swerved to avoid, and scream at, a motorcycle blazing a trail in the Mumbai traffic. My first time outside of New York and I end up in traffic that's somehow worse than Canal in rush hour.

"My parents took us all over. I was thirteen - thirteen? No, twelve - when they took me to Paris for my birthday. I honestly don't know how they did it. How did they keep up with a house and boarding school? I always thought we grew up, like, pretty poor..." Jocelyn was enjoying the conversation with herself.

Sada, my college roommate and our guide, sat between us. She met us at the airport the night before and let us crash at her apartment in Juhu. I wanted to be angry at her for making me get on a 15-hour plane ride with Jocelyn, her childhood-boarding school friend. But I flew halfway around the world to see Sada and it was damn good to see her again.

Jocelyn latched onto Sada’s arm and pulled her in close. “Babe, where are the slums?”

“Sorry?” asked Sada.

“The – Dillon, you know – the slums. How do we get in?”

Uncertain why I was being dragged into it, I stayed silent. The driver scrunched up his face at us in the rearview mirror.

“People live there, Jocelyn. They don’t sell tickets.”

“I was hoping to get some good shots.” Jocelyn pouted, her lips pursing into a duckface.

The cab dropped us at an art gallery – still unsure of the exact location – in a renovated warehouse. Outside, it was a dingy brown building with large iron doors. Inside, the hollowed-out shell was whitewashed and sterile. It smelled of must and incense, and the smallest sound echoed into every crevice.

“I’ve been meaning to get here,” said Sada. “You’re the push I needed.”

The main exhibit was a photo series of a ship graveyard in Bangladesh. Big, rusting hulks anchored in the sand with nowhere to go and nothing to do. Workers dissected them carelessly - a dangerous job reserved for the lowest caste. One of the photos was a long exposure of a team removing a ship’s hull. The sweeping streaks of rusted iron created a firestorm of orange across the frame. The artist, a Bombay local, said of the workers, “They are the bravest, wisest, most frightening people in the world.”

I could feel everyone’s eyes on us as we entered, wandered and exited the gallery. I didn’t know how to be a tourist – how do you exist and just be in a place you’ve never been? Where you don’t know anyone and no one knows you? I did know I didn’t want to be another white, American tourist looking for their big spiritual awakening. Buying all the trinkets and falling into every tourist trap was not my speed. Jocelyn had other opinions. Luckily, we had Sada.

“Come on! We can walk to the Gateway from here,” said Sada. “You both have cash?”

“Oh.” I had no cash at all - no rupees that is. Rookie mistake. “Is there an ATM somewhere? I read it was better to do that because the airports give bad rates.”

“No! Don’t do that!” said Jocelyn. “You’ll get hit with all the foreign transaction fees. You know, the best thing to do – ”

“It’s okay yaar, I have a guy,” said Sada.

We followed her down the sidewalk and through intersections. Driving through Mumbai traffic was chaotic. Walking through it was a far different experience. No waiting for stop signs and white Walk signals. One needed only to walk with enough determination and a hand up to say Don’t run me over. Try that on Eastern Parkway and you would not live to tell the tale.

In an alley in Colaba, we came to a kiosk large enough for one person to stand inside. A man with a bushy mustache and smoking a hand-rolled cigarette was rearranging his wares. Benches and tables in front of the kiosk covered in pashminas of colors I didn’t know existed. Marigolds and dahlias accented every corner. Inside the kiosk, cameras, cameras and cameras of all kinds. Some in boxes, some on wall hooks, and some dangling from the ceiling on strings.

“Namaste, Daanish.”

“Ah Sada, my most favorite top customer!” said Daanish.

They talked for a few minutes in Hindi, while Jocelyn and I tried our best not to stand out like sore thumbs. We were unsuccessful. Their conversation escalated into laughter and ended when Daanish waved me over as he walked into the black doorway next to the kiosk. Sada followed. The three of us were crammed into the shade of the doorway, hot breath on each other’s faces.

“Alright, Dillon,” said Sada. “How much do you need?”

I fumbled through my pockets searching for all the American dollars I had. Daanish snatched it out of my hands almost as fast as I could pull it from my pocket. He ran his fingertips through it a few times, his eyes never leaving my face.

“American, eh?”

“You give good price…” Sada warned with her finger pointed at Daanish.

“Always for you yar,” said Daanish. He counted the rupees in front of me and put them in my hand. “Not in your pocket.”

I shoved the cash into my backpack instead as we walked out of the doorway and into the sunlight.

“You need film? Or a camera? For the Kodak moment! I have all the best,” said Daanish. He took the cigarette from his mouth and tapped the ashes on the ground in front of us. Sada wasn’t interested, which meant we weren’t either.

“Namaste,” said Daanish with hands together in front of his chest. Sada did the same. Jocelyn and I copied her, but Sada was already off, back toward the main road.

We didn’t have much further to go according to Sada. Around the corner, a quick left, another right, up another block and there we saw three banyan trees. Underneath the monumental trees, people lined up and filled the skinny street. The three of us crammed in together and waited to get to the Gateway of India. The stone archway was like that of Washington Square or Grand Army Plaza. A fleet of candy-colored ferries waited on the other side, in the bay, to make the journey to Elephanta Island – our destination.

While we waited, photographers paced up and down the line searching for customers. They carried their own printers and offered instant prints. Two for one and five for two. A woman ahead of us in line peeked over her shoulder at us and froze. Tears streamed down her face. Her hands shook as she reached out and held my face. Sada translated.

“She wants to take a picture with you, Dillon,” said Sada.

“Me? Why me? And why is she holding my face? I really don’t like -” I grabbed the woman’s hands, but she wouldn’t let go.

“She’s never, um, seen a white person before…”

“I’m sorry?” I asked.

“She’s saved her whole life to come to the city, to come to Bombay,” Sada translated. “She’s always wanted to see how all the rich people live because everyone in her village is poor. Her mother told her stories about the caves at Elephanta and she’s always dreamed of finally seeing them. This is me talking now – if you don’t want to do it, you don’t have to.”

“I…don’t mind,” I said. One photo. It was more important to her than it was to me.

Sada gave the woman the okay. The woman threw her arms around me and cried more. Two of the photographers rushed over to take photos before anyone even paid them. Seconds later we all had photos shoved in our faces of a crying woman hugging an awkward me. The line moved forward and I forked over some cash, not knowing how much was enough.

The ferry was 120 rupees, which was about three dollars. Sada paid the extra 60 rupees to sit on the upper deck. Jocelyn and I followed suit. We seated ourselves at the back of the top deck and watched the Gateway get smaller as the ferry pulled away.

“You’ll get a better view from up here, trust me,” said Sada.

Top deck or bottom deck, the view would have been the same either way. But the wind was cool on my skin. It was a much-needed reprieve from the humid furnace of the city.

We passed abandoned forts, complexes and docks scattered throughout the harbor. One of the rundown way-stations looked like a battered version of Captain Nemo’s Nautilus. The industrial ruin melted into the rusty bay.

“Are the temples on Elephanta, like, super important?” asked Jocelyn.

“As important as any other, I guess,” said Sada.

“They’re part of your history though?” I asked.

“They are. But for me I just look at them and it’s like, Great. It’s a wall. What’s next?” said Sada.

At first, our destination was a speck of dust on the horizon. After an hour of cutting across the bay, the imposing green island loomed over us. The island’s dock had enough room for one ferry. With three ferries in the water there was no time for taking turns. They played a graceful, choreographed game of bumper boats as they lined up side by side. The path to the dock led us through a precarious obstacle course of gangplanks. One wrong move and you were in the water, crushed between the ferries. At the end of the dock sat a miniature train on miniature tracks. The train cars vibrated with excitement, waiting to cart passengers across the island. Each train car sat four people, but no one cared about comfort. Seven, eight, nine people could fit if they tried. And they did. We watched the overflowing train pass us by.

As we shuffled down the cement path, a group of laborers trudged through the shallows in their bare feet. The tree-covered mountain cast a shadow over them. They were hard at work resurrecting an old ferry. The whales of their mallets bounced off the cement, out into the nothingness of the sea air. Vendors and shop stalls appeared out of thin air as we continued down the path. Beaded jewelry, hand woven scarves, and useless trinkets. Mementos for the journey we hadn't made yet. Sada gravitated to a table covered in beaded jewelry. She added to her wrist full of bangles and bracelets. Jocelyn stopped at a table of stone carvings

“Wouldn’t this look great in my new apartment?” said Jocelyn. She held up a candle stand with elephants carved into the sides. Her eyes passed over some elephant engraved coasters. “Oh, and these too.”

At the end of the path, a mustached guard stood by a turnstile. He checked our bags for spray paint. Then the courtyard, the bathrooms, and a large green sign which read, Beware of Monkey's. We giggled at the error, but the apostrophe was not a mistake. The tickets were at the top of the mountain, up a staircase of a thousand steps. The exhaustion set in even before we began. The wind in the tree canopy and the low rumble of shuffling were peaceful. Soon the vendors flanked us on both sides of the stairs and the foot traffic slowed to a crawl.

The crowd became its own entity, ebbing and flowing with the interest of the vendors. Everyone piled on the trinkets and souvenirs. Everyone's bags got bigger, everyone's bags got heavier and no one saved a thought for the journey home. Soon tarps and canvas sheets covered the path to protect us from the rain and the grabby monkeys. The humidity fogged my glasses, not ideal for climbing a mountain of stairs.

“Do you see your family often?” asked Sada

“They all think I’m this starving artist. They don’t get it, you know? I’m doing everything I can to stay on this path I started on, but it’s not what they think is right for me,” said Jocelyn.

“Well, is that right for? You don’t have to stay the course because it’s where you started. There’s no reason why you can’t change paths…”

Their conversation trailed off. I focused on choosing each step forward with care, careful not to stumble. Ahead of me, Jocelyn and Sada disappeared into the jaws of the crowd. I tried to catch up, elbowing through the sea of people. The more I fought the tide, the further away it pushed me. As the suffocating, humid air filled my lungs each breath felt like I was drowning. The tide pushed me this way and that until I felt the sea part.

The crowd split into two lanes around an old woman, a boulder in the morning surf. She was unfazed by the traffic. Her hair was stark white with a one remaining streak black. The frayed red and gold sari draped around her shone like the sun after a rainy day. With a deep breath, I shuffled forward. The woman's deep greens eyes were inches away from my hazel eyes. She smelled of jasmine and coconut and her smile stretched from ear to ear, revealing a few missing teeth. She shoved something cold into my hand, something made of stone. She slipped past me without a word. As my eyes met my palm, there sat a limestone elephant no bigger than a thimble. It was missing a leg.

I turned on my heel, but the green-eyed woman was gone. Lost in the crowd. Behind me, the parted sea had closed up and the tide was pushing me back down the stairs. I broke through the wave of bodies to sit on the edge of the steps and catch my breath. There was an opening in the wall of tattered sheets and tarps. I held the three-legged elephant up to the light leaking in. The little stone carving was far from new. The side with the missing leg was clean and sharp; the other side dark with edges smoothed down by time.

“Dillon? Dillon?!” I could hear Sada’s voice moving closer. “I knew one of you’d get lost.” She was clearing a path for Jocelyn, who was now lugging two tote bags full of souvenirs. I slid the elephant in my pocket and joined them.

“Would you mind taking one of these?” asked Jocelyn. She handed me one of her tote bags. Strain marks on her shoulders were visible where the straps were.

I threw the bag over my shoulder. There was something made of stone at the bottom of the bag, which kept banging into my hip bone.

At the top of the mountain stood a gated entrance to the temples and caves. The fee to enter was less than a dollar for locals. It was ten for foreigners. We paid for our tickets and in we went. As we walked through the gate, one of the scruffier monkeys swooped down in front of Jocelyn and swiped at her bag. In preparation for our trip, we had read tips on how to deal with the monkeys. One expert said make yourself seem as big as possible; it shows your dominance. The expert forgot to mention the monkeys are experts of the same method. The monkey kicked off of its front hands with a loud yelp and stood up on its legs.

“Uh, Sada?” said Jocelyn. “Dillon?”

Every step backwards Jocelyn took, the monkey hopped forward to meet her. It beat its chest and yelped. Yelling louder than the monkey, I ran toward him waving my arms above my head.

“No! No! No! Back! No! Get out of here!” I didn’t even know what I was saying. The words fell out. It was enough to send the monkey leaping into the trees. It was our chance for a getaway and we ran for the entrance of the caves. The something-made-of-stone in the tote bag banged into my hip bone even harder than before. It was definitely going to leave a bruise.

The mouth of the caves was at the end of a cobblestone path. Thin grass with black rock peeking through grew around the path and up the cliff face. Four stone pillars greeted visitors as they crossed the threshold of the cave. On either end of the entrance, a sculpture of Shiva carved into the wall. Three Indian men – not Mumbaikars – at the edge of the cave entrance aimed their smartphones up at the carving. One of them spotted Jocelyn.

“Excuse me, miss. Could we take a picture with you?” one of them asked.

“Sure!” Jocelyn threw one hand on her hip and the other held on tight to her tote bag.

Sada groaned and stood to the side.

“And you too?” they asked me.

This is not what we came here for, but I didn’t want to be disrespectful. We – at least Jocelyn and I – were visitors after all. Arms tight to my side, hands crossed in front of me – I leaned into the frame with a forced smile. Each of them took turns posing in the photo and making the photo. This went on long enough for more tourists to jump in. They wanted their chance on the red carpet too like we were celebrities on the red carpet.

“Okay, that’s enough,” said Sada. She ploughed through the group surrounding Jocelyn and I, and pulled us away.

“Sada, it’s fine,” said Jocelyn. “I really don’t mind.”

“I mind! You’re my guests and it’s so disrespectful, toward both of you and me too,” said Sada. “I didn’t sit on that ferry for an hour for this.”

“How though? If we don’t mind and they ask, isn’t it alright?” asked Jocelyn.

Sada closed her eyes and muttered something to herself. “Just…let’s go. We don’t have a lot of time.”

The tension in my body released as we left the crowd behind us and headed into the caves. Beyond the threshold, daylight fell off into complete darkness. The only way was forward. My eyes adjusted once we wandered in the pitch-dark long enough. That's when I saw them. Shadows danced over the basalt walls of the great cave. The intricate shrines came alive, Shiva's many stories played out in front of our eyes. To my right, two parents and their toddler stared up at the walls, lost in their beauty.

The path through the caves led past a waterfall into a gorge at the heart of the mountain. I stood at the center of the gorge and the sun beat down on my skin. The warmth dried away the mist of the cave. I could smell the wet soil as visitors kicked it around with each step. The slightest movement ricocheted off the black rock walls surrounding me. It was loud and quiet at the same time. Ahead lay the entrance to a smaller temple. I felt a cold tightness rush through my chest. I reached into my pocket and ran my finger over where the elephant's missing leg was once attached. I'd never felt more anxious and out of place, yet so at peace and at home.

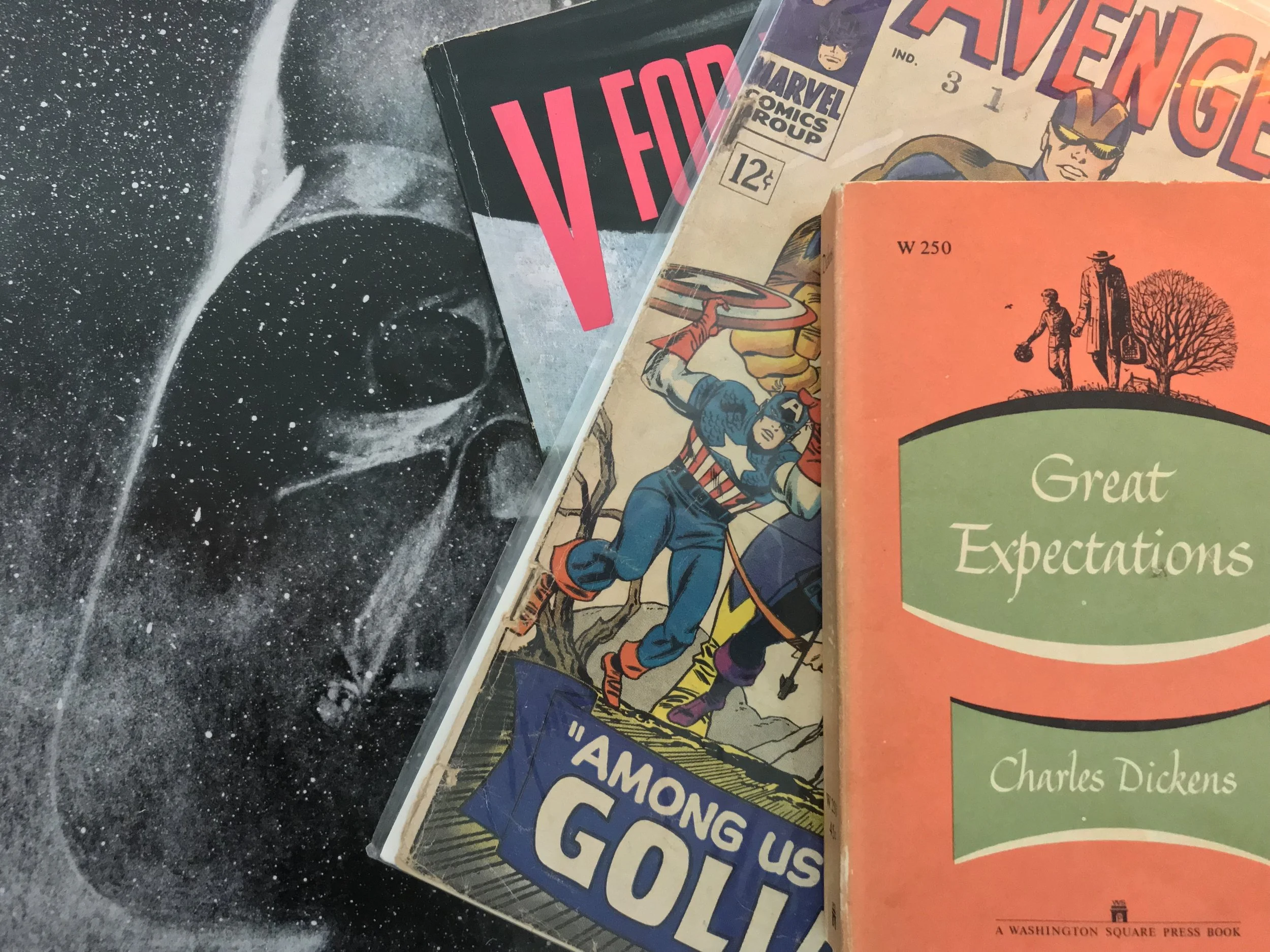

Jocelyn led Sada into the smaller temple. I didn't move. I wanted to hold onto that moment for as long as possible. I'm uncertain how long I stood there, lost in that moment. If it was for eternity, it wasn't long enough. The next crowd poured into the gorge and I had no choice but to let go. I shuffled up the steps of the small temple, hand still in my pocket and the elephant nestled in my sweaty palm. People rested on the steps and the archways of the temple. A few read books, most took photos, and the rest enjoyed the solitude.

The smaller temple was bare and plain. The unanimous disappointment from the crowd was audible. I shuffled along with the foot traffic and jumped out before heading back down the stairs. No one else noticed the remains of wall sculptures in the wings of the temple's entrance. Most of the remains were so weathered it was near impossible to discern their shape. One jumped out at me - a soldier with a pointed helmet. Where once was a face, now stood a featureless, smooth stone. I could feel its blank stare boring through me. I tightened my grip on the elephant. Sada put her hand on my arm and I jumped.

“You okay?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said. I could barely get the word out.

It was time to go, but I could not pull my eyes away until the absolute, last second.

The last ferry was in less than an hour and we still had to make it down the mountain. Moving back through the caves, I kept a firm grasp on the elephant in my pocket. Through the gates and down the stairs. The journey up the mountain was an eternity. The return trip felt like seconds. The vendors flew by faster than I could take them in. We took turns passing around the overflowing tote bags. I needed both hands and let go of the elephant in my pocket.

One last stop at the restroom, where a cow heading for a garbage bin came within inches of trampling me. I moved out of the way in time. I could smell the garland of marigolds around its neck as it tottered by. We ran to catch the miniature train. Everyone else had the same idea as us. Each car was full with passengers finding every bit of open space. We sprinted all the way to the docks, where the ferries had already completed their game of bumper cars. The gangplank obstacle course beckoned us.

From the dock, we could see the blue haze of the city rising out of the water. The chaos was waiting for us. On the ferry, it felt like we were returning with more passengers than we'd arrived with. It was hard to breathe, let alone think, between the jam of bodies. The claustrophobic ride across the bay wore down Jocelyn's patience by the second. A passenger looking for a seat wedged himself between Jocelyn and another passenger. He may as well have planted himself in her lap. Jocelyn clutched her souvenirs closer and jumped up. The passenger slid into the seat and another passenger did the same.

"Sit here," I said, relinquishing my seat. "I don’t think he meant anything by it."

"Oh yeah, sit in some stranger's lap. Real nice way to treat people," said Jocelyn. She shifted her bags onto her lap as a barrier between her and the rest of the ferry.

"Things can get a little crowded sometimes. We don’t waste any space here," said Sada.

The closer we moved to the city, the faster those moments of peace on the island fell away. I reached into my pocket for the elephant. My heart sank in the half-second before my fingers brushed against its trunk. Inspecting it in the hard light of the setting sun, I could see every intricate detail of the stone. It was beautiful, yet simple.

The ferry docked in the main harbor as the sun slipped behind the horizon. The city's nightlife was beginning to wake up. Taxis sped up to the departing passengers, hustling for fares. Street carts peddled bottled water and fresh-cut mango. The photographers, printers in hand, had cut their prices to four for one – final offer. Behind us, the soft lapping of the ocean against the bulkhead. The creak of the ferries swaying in the tide. The shuffling of the foot traffic. It was both loud and quiet at the same time. We squeezed through the crowd toward the taxis and passed a group of people praying at the base of a banyan tree. It glowed with the orange flicker of the candles stuck into its nooks and crevices.

The three of us, drenched in sweat and exhausted, jumped in a cab back to Juhu Beach. Weaving up through the city and then along the beach, we watched the city come alive with lights of every color imaginable. Finally sitting down after a long day, it was to fight off sleep. The cab jerked to a stop when we made it to Juhu and I came out of my half-asleep daze. At the end of the street, rainbow-colored lights glowed and flashed on the beach. The faint smell of the ocean mixed and street food crossed wafted through the air.

“What’s that?” asked Jocelyn.

“Juhu Beach. It’s a good time if you’re in the mood. The water is usually pretty calming.” asked Sada.

“I could use a little calm,” I said.

“We can go if you’re up for it.”

“I could also use a bed. Bed feels calm just thinking about it.”

“I could use a drink,” said Jocelyn.

“Never mind, I second that. Who said anything about bed? Who needs a bed?”

“That can be arranged.”

Sada led us to a bar a few blocks away – her regular bar. The warm lighting and teak wood highlights gave it a cozy feeling. Photos of hard shadows and close-ups of architectural details covered the back wall. All the frames, placed with precision, juxtaposed each other. At the center of the frames was a single, round mirror. It was like a porthole into a different world. I caught my reflection. The sweat stains on my tank top had dried and my hair was a frizzy mess. My face, though, didn’t look like my face. It was me, but not me. I couldn’t put my finger on it. We sat right at the bar and Jocelyn put her card down immediately.

“First round is on me,” said Jocelyn.

“That’s not necessary, Joss,” said Sada, cash in hand.

“It’s the least I can do,” said Jocelyn.

“And I got next round,” I said, pushing her hand down. “Your money’s no good here, lady.”

We toasted to a good day, a good trip and good friends. Some of Sada’s friends showed up and she introduced us. Made the rounds, exchanged pleasantries. The usual type of linguistic gymnastics you do, no matter where you go.

“How’s it living in Mumbai?”

“How’s it in New York?”

“Manhattan’s too expensive, I’m out in Brooklyn.”

“Mumbai’s dead, ya.”

“I don’t know. I guess I could head West, but I like seasons.”

“I’m kind of stuck here for now, but I’m saving up for London.”

The bar filled up fast. The calm silence was soon replaced by constant, humming chatter. After a while, it all started to sound the same. It was easy to feel cut off, isolated, like at the eye of a storm. I reached into my pocket and grasped the elephant in my clammy hand. Sada put her hand on my shoulder.

“Hey, are you alright?” she asked.

“Yeah.” Deep breath. “Yeah, I’m fine.”

“Well…smile!”

We throw arms around each other – me, Sada, Jocelyn, Sada’s regular crowd – smiling in unison for a photo, drinks in hand.